Introduction

I’m a Neovim person. I’m not gonna hide it anymore, and I’m not ashamed of it. I like this tool so much that I would rather build custom tools rather than switch to an alternative with existing integration. In this case I’m talking about using Neovim with Unity instead of Rider.

Neovim has LSP (Language Server Protocol) support, but it is difficult to get a good Unity integration form a language server that was designed to work with C# in .NET. Omnisharp, the language server I’m using, has issues that make it difficult to work with Unity efficiently. (Maybe it’s just my subjective view, if you know how to make it better let me know). I would love to have a proper ReSharper integration with Neovim.

But today is not about wishes, it’s about creating. I figured that I lack two basic things:

- Trigger the compilation process in Unity from Neovim

- Display Unity’s logs in Neovim []. Independently these features weren’t a problem for me, but I didn’t know how to connect them together, besides using a web socket. So I started my research. I spend quite a lot of time trying to understand the basics of inter-process communication, and with this entry I’m I want to share what I learned.

I’m going to place small code snippets in C++, but they are mostly as a fun fact, so don’t feel discouraged if you aren’t comfortable with Cpp.

Hope you enjoy this one.

Even though I have two monitors I don’t want to just with my eyesight between them. I’m alright with fixing problems created by my own laziness.

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Inter-process communication

Inter-process communication is a scenario where to or more processes on the same machine want to communicate with each other. Exchanging data between programs is a common thing, in my mind it was typically done with programs that run on different machines. Internet is the obvious example for this, where our devices serve as clients in this complicated web of connections. But IPC (inter-process communication) happens more often then you would think, or as I thought.

The Wikipedia article on this topics lists 11 different ways of communication between processes:

- Files

- Communications file

- Sockets

- Unix domain socket

- Message queue

- Anonymous pipe

- Named pipe

- Shared memory

- Message passing

- Memory-mapped file I don’t want to talk about all of them (but check them out, it’s a cool piece of history), but I will share my thoughts about three of them.

To make this more specific let’s assume that there are two processes A and B that want to communicate with each other. The communication ideally should be in both directions but we could use two of the same IPC mechanisms to make it work.

Let’s start with the natural one, files.

File

Files are the most basic thing in a computer. I think that everyone who has ever touched a computer knows what they are. Files are used for transferring information, because they are information. The exchange is usually turn-based, one program saves a file, another reads it; it doesn’t have to be that way. Processes A and B, could open a file, and use it as a shared resource.

The process of using files as IPC is straight forward, but before we even think about exchanging data, we have to serialize it. Some languages, like C#, have a builtin way of serializing objects, but in other languages we have to get creative. Or just use JSON. Nonetheless, serialization is a requirement that has to be thought about.

Both A and B can open up and read the file without any issues, modifying is a bit more complicated. File I/O (input & output) are not atomic operations, which means they take time. Let’s Imagine A starts a long writing procedure:

//just_a_file.txt

AAA

BBB

CCC

DDD <- A

\EOF Process A want to write down the whole alphabet, and it’s already at D. In that moment process B opens the file. Since this is the only way for those two guys to communicate, B has no information about A’s status. Now, it start to read the file:

//just_a_file.txt

AAA <-B

BBB

CCC

DDD

EEE <-A

\EOF Depending on I/O speed, A might be able to keep writing letters as B reads them. That would make the transfer of data valid. Although possible, it is not very likely. Files are usually kept open as a program does internal work, it’s more likely that B will catch up to A:

//just_a_file.txt

AAA

BBB

CCC

DDD

EEE

FFF

GGG <-A

\EOF <-BFrom the perspective of proces B, it has all the information A wanted to pass to it, which we know is not true.

The case I’m describing is known as a data-race, which is related to multi-threaded programming. At first it might not be obvious we are enduing in multi-threaded programming, but we are. The OS’s scheduler dynamically decides for how long and on which core a process runs. Two processes might execute on the same core sequentially, or they might run on separate cores that execute in parallel.

Since we can’t predict how A or B will be run, we have to assume that we are in a multi-threaded environment. Now, there’s a simple solution to this problem, we have to lock the file while a process is using it. A locking mechanism, or simply a lock, is a way of limiting access to a resource. There are different kinds of locks, but here mutex is enough. The name mutex comes from mutual exclusion. And it works by limiting all access to a resource, it cannot be read or written to.

Back to our example, before B will try to read the file, it will try to obtain the lock. If the lock is already in place, it will wait. When A finishes writing, it will unlock the file for B to use.

All modern operating systems support file locking. For Unix-based OS that would be https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/flock.2.html and for Windows: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/fileapi/nf-fileapi-lockfileex

Memory-mapped files

Files can work for exchanging information, but we can make this better. Instead of locking, reading/writing, unlocking, we can ask the kernel to map a file onto virtual memory and give us a pointer to that memory. This is called memory-mapped file, or file mapping.

How do you use it? Unfortunately, we left the realm of C++‘s Standard Library and we have to use system calls. Writing platform dependent code is difficult, but there are good reasons to do the work.

On Linux we can create a memory mapping by using the mmap function:

void *mmap(void addr[length], size_t length, int prot, int flags, int fd, off_t offset); //#include <sys/mman.h>It does look a bit frightening, doesn’t it? It gets clearer once get some context; like if we wanted to read the content of a file:

... // Parts of the code that manage getting the file descriptor and size of the file

void* map = mmap(nullptr, filesize, PROT_READ, MAP_SHARED, fileDescriptor, 0);

if (map == MAP_FAILED) {

return 1;

}

const char* data = static_cast<const char*>(map);

std::cout << "Reader sees message: \n" << data << std::endl;- The first argument, of type

void addr[length]is a pointer, that works as a suggestion of location. The kernel will try to fit the mapping at that address but if it fails, or the address isNULLthen the OS will chose an address.q size_t lengthdefines the length of the mapping. Which if we want to read the whole file equals to the file size.PROT_READandMAP_SHAREDare flags that define, what should happen to the memory (will it be read, written to, executed, or nothing at all), and whether the changes should be shown to other processes (shared or private).- File descriptors are a way of managing files in Linux. They work as unique handles to a file, but they are unique only within the process that asked for it.

- The last parameter is an offset applied to the pointer, if we wanted to ignore a part of the file.

The function returns a pointer to the start of the file, we can do with that memory what we want. In the code snippet above, I changed the type of the pointer to char*. I know that there’s human-readable data in there; but we can do more than that.

When I talked about files, I mentioned two problems with them:

- Serialization - we need change representation of the data to save it.

- Data-races - files are susceptant to data-races and need a locking mechanism.

But there’s another one: performance. In operating system there’s an important separation between all processes. The programs that we usually run exist in a user-space, here the processes have very little access to resources on the computer. We say that they have very few privileges. On the other hand, there’s a kernel space, where the kernel is executed and so are the drivers to all the devices. Processes run in kernel-space have access to almost anything (technically, only the kernel has access to everything, drivers run in a different protection ring)

Accessing the hard drive is a privileged operation that user-space process don’t have access to. Every request to access a hardware device goes through the kernel, which then passes that request to the device driver, and comes back with the result. This will happen when our process is running, the scheduler will suspend our process, and switch to execute the kernel. This is called mode switching and can have big impact on the performance of our applications. Opening a file, reading, and writing are all syscalls (calls to the kernel API) and we should do them as little as possible. It blew my mind when I first read about it. I didn’t realize, that applications are completely stopped when you access the kernel. This means that not only we have to think about the performance of the code that we write, but also about how we access the kernel.

Luckily, memory-mapping help us with all three issues. Memory-mapped files have this cool feature, that allows us to use a shared data type. Here I defined a SharedData struct that holds a mutex and some information that we want to pass between the processes:

#include <pthread.h>

#include <string>

#include <cstring>

struct SharedData {

// The C++ std::mutex is NOT process-shared, so we use the POSIX C type.

pthread_mutex_t lock;

// 2. The shared data protected by the lock.

int counter;

char message[256];

};This is a great advantage over files, since we don’t have to serialize everything; we can even store the lock inside the struct. (On Windows there should be no need for synchronization). Although, there are limits to what we can pass within this shared type. The general rule is that the struct or class that we use has to be a Plain Old Data (POD) type. (you can read more about them here)

... // Parts of the code that manage getting the file descriptor and size of the file

void* map = mmap(nullptr, filesize, PROT_READ, MAP_SHARED, fileDescriptor, 0);

if (map == MAP_FAILED) {

return 1;

}

SharedData* sharedData = static_cast<SharedData*>(map);

//Lcok the mutex

std::cout << "Reader sees message: \n" << sharedData->message << std::endl;

//Unlock the mutexNow, why is this approach faster than files?

Behind the scenes

Any file operation require a call from a process to kernel. The kernel then stops the execution of the running process, performs the requested task and provides the application with the result. This happens for reads, writes and mmap. In case of standard I/O, the syscall happens every time we need to do the actual read or write. Memory mapping is a bit different, because we only need to call the kernel to set up the mapping.

![[WRITING TO LEARN/Entries/10. Inter-process Communication/Inter-process Communciation.excalidraw.md#^clippedframe=I1pJeLnlazZMRpfs0YBNM|1000]]

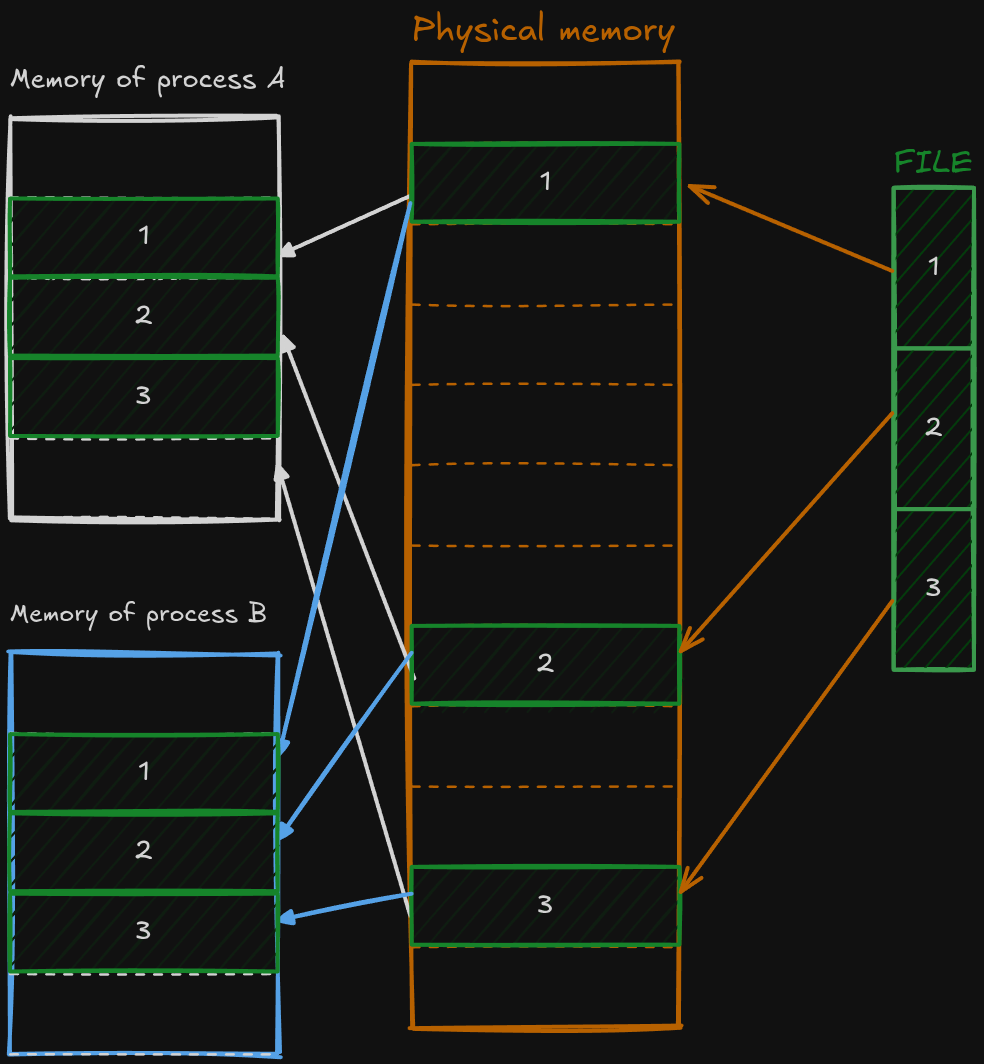

Each process has its own memory called virtual memory (it’s an interesting concept, but outside of the scope of this blog post). When we create a file mapping the kernel allocates memory for that file in RAM. RAM and virtual memory are split into blocks, called page frames and pages in this order. Each block’s usually around 4 KB. Figure 1 shows how this mapping would work.

There’s more nuance to it, because the data will not be loaded until is requested by the process, but that’s not important right now. What’s important is that the memory mapping can be created once and then used without any overhead from switching between user-mode and kernel-mode.

Interesting feature of memory-mapping

Honestly, I think of Linux as one of the best examples of great design in programming. Design patterns are also cool, but they are tiny when compared to the whole Unix philosophy. My love to Linux started with the terminal. It’s not perfect by all means and it shouldn’t be used as the only way to interact with a computer; but it is a good design. The core ideas that drive it, the sheer amount of possibilities that we have through scripting, and how the programs can interact with each other is just wonderful.

But as I was writing this article I started reading more and more about how the system works, and I realized that the terminal is the tip of the awesome iceberg. Everything is a file on Unix. It’s not only a weird sentence, but also an approach taken by the designers of Unix to deal with I/O. Data (regular files), directories (are a special file), devices, processes, sockets; they are all represented as files on the operating system.

This brings us to a very neat feature of this approach; a memory-mapping can be made to any file, which means that we can create for example a memory mapping of a device. [9] How would this work? I’m no specialist in this matter but this is how I see it: in order to communicate with a piece of hardware the operating system needs a driver. Linux gives the author of the driver the possibility to define what should happen if a mapping is created.

Games are a great example of where this is useful. Assuming that games try to update the frame at least 30 times per second, which is very low for today’s standards. This means that 30 times a second we are going to update the simulation state, prepare the data for rendering and somehow transport this data to a GPU. Issuing a syscall on top of the very expensive calculation done by the game would have catastrophic consequences on the performance. Instead of issuing a system call each time the game wants to update the graphics, we could map GPU’s memory onto the process memory. This gives us near instant access to memory and we have to worry only about the calculations that are done by the game.

Pipes

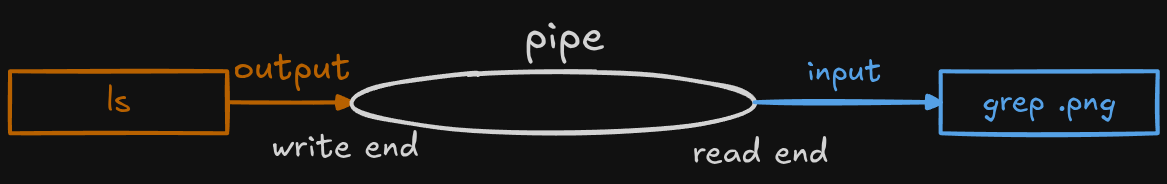

The last but not least in this IPC saga are pipes. Interestingly enough, they are the oldest way of communication between processes [11]. The idea behind them is simple: connect the standard output of one process with the standard input of another process. They can work as a bridge between related and unrelated processes, I will explain what I mean by that it a bit. This bridge is not a to way street, if you want the information to go both ways, you have to make another bridge.

Most of you guys are should be familiar with this guy: | . That’s also a pipe. But pipe, as in the feature of the kernel, and the command line pipe (or shell pipe) are not exactly the same.

The shell pipe | is a program that takes two commands as parameters runs them, and connects their input and output. It uses kernel pipes to do so.

Note: To avoid confusion, when I refer to a pipe I have in mind a kernel pipe.

Originally pipes, known as anonymous pipes, were only part of the kernel. Just like a memory mapping, you could create one with a system call:

int pipe(int pipefd[2]); //#include <unistd.h>The function pipe fills the pipefd array with file descriptors that point to the pipe. The first element refers to the read end the second one is the write end. Since file descriptors are process relative, once created, they are usable only to the process that created it and to its children. That’s why pipes work only with related processes.

When a process calls the pipe() syscall, underneath the hood kernel allocates some memory for the newly created pipe. Each pipe has a capacity of 16 page frames, which are used as a circular buffer. A page is of memory, which means that a pipe can hold of unique information before the oldest is overwritten. The writing process writes information while the reading process wipes it off. [12]

How do they compare to files? Well, like with files the data has to be serialized in order to pass it a pipe. The performance is better, we need to make a syscall to create the pipe. We cannot write to the memory directly, because we have a file descriptor not a pointer, so we have to use write() and read() syscalls. But the file descriptors are just a representation, there’re no files on the hard drive. The kernel just uses them to access the memory that it has allocated for the circular buffer. This operation is faster, than accessing a real file.

What about synchronization? Do we need a locking mechanism or not? That’s depends on how much data we are sending at once, in the man pages of pipe we can read:

POSIX.1 says that writes of less than **PIPE_BUF** bytes must be

atomic: the output data is written to the pipe as a contiguous

sequence. Writes of more than **PIPE_BUF** bytes may be nonatomic:

the kernel may interleave the data with data written by other

processes.This means that for small messages we don’t have to worry about any synchronization, but if a payload exceeds the size of PIPE_BUF we don’t know what will happen. On Linux PIPE_BUF is bytes, which is exactly the size of a page frame. Writes and reads to a pipe are atomic unless we exceed the size of one page frame.

FIFO

Linux offers another kind of pipes, called FIFO or named pipe. We can use FIFOs like regular pipes, but we can do it without being related to another process. FIFOs have a file representation, the name of the file serves as an address to the pipe. Nothing is stored in this file, it is used only for connecting to the pipe, data flows through a kernel buffer, just like with a regular pipe.

int mkfifo(const char *path, mode_t mode); // #include <sys/stat.h>They might seem like not much but this small difference in operation allows them to be used as a means of communications between applications that aren’t dependent on each other, for example: a client and a server. I think that they can be useful for applications that allow creating extensions. I used FIFOs for my plugin. I used two named pipes for communication between Neovim and Unity. Unity plugin creates the pipes and awaits a connection. Upon connecting Unity starts sending all the logging information to the client, and awaits any commands that it might request. On the Neovim side, I’ve created a window for displaying the logs, and commands to build a game and refresh the editor.

Closing speech.

This article came up as a result of my trying to create the plugin for Neovim and Unity, and I learned a lot. Going down the Linux rabbit hole was a cool experience and I hope that I demystified the topics a bit for you.

I would like to live you with this: don’t get stuck in the tooling that you have. Sometimes I see developers lose themselves in their frameworks or tool with out any intent to go outside them. I see this mostly with game developers. Some of them treat game engines as their life vessel on a high sea; they are scared that they are going to drown if they step out a bit.

So go, learn and experiment, set foot onto unknown territory.

Bibliography

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Inter-process_communication

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Process_(computing)

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/ipc/interprocess-communications?redirectedfrom=MSDN#using-pipes-for-ipc

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/ipc/interprocess-communications?redirectedfrom=MSDN#using-a-file-mapping-for-ipc

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/memory/file-mapping

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/rpc/microsoft-rpc-components

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/ipc/named-pipes

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Named_pipe

- https://linux-kernel-labs.github.io/refs/heads/master/labs/memory_mapping.html#device-driver-memory-mapping

- https://sbrksb.github.io/2021/01/05/pipes.html

- Michael Kerrisk. 2010. The Linux Programming Interface: A Linux and UNIX System Programming Handbook (1st. ed.). No Starch Press, USA.

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man7/pipe.7.html

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/mkfifo.3.html